Nestled amidst the rugged terrain of Rajasthan, where the desert’s golden sands meet the endless azure sky, lies a marvel that transcends time and transports you to a realm of ethereal beauty. Imagine stepping into a realm where white marble pillars rise like ivory sentinels, where the air is imbued with a sense of serenity, and where history’s whispers echo through every meticulously carved corner. Welcome to the enchanted world of Ranakpur Temple, where divinity meets design in a symphony of architectural mastery.

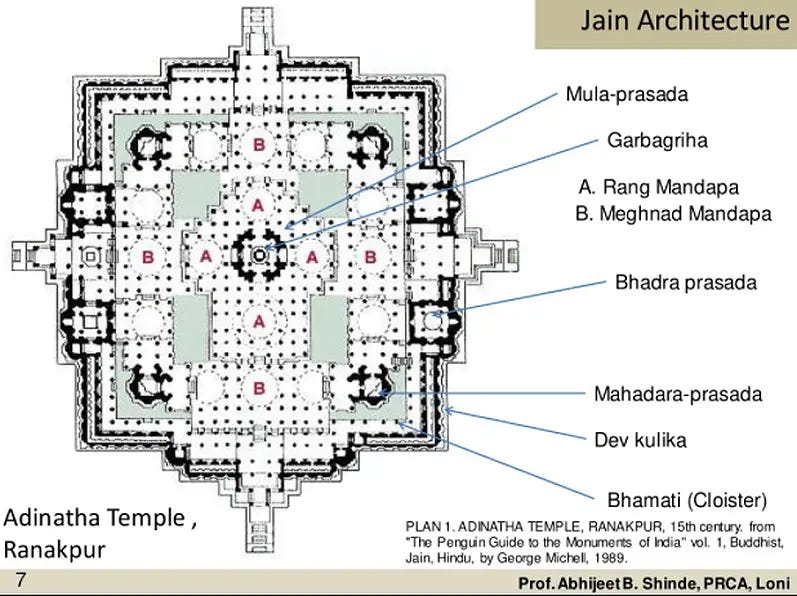

As you approach this sacred haven, you’ll be greeted not by a single entrance but by four, beckoning you to explore the mysteries that lie within. Each entrance reveals a facet of the temple’s magnificence, like a gemstone refracting light in a kaleidoscope of colors. And at its heart stands Chaumukha, the four-faced marvel, where the Tirthankara Adinatha gazes in serene contemplation in all directions.

But it’s not just the grandeur that makes Ranakpur Temple an enigma; it’s the stories etched in its marble, the devotion that echoes in its halls, and the intricate carvings that seem to breathe life into stone. Here, the past intertwines with the present, and spirituality transcends the boundaries of time.

Rana Kumbha was a prominent ruler of the Mewar dynasty (1433 to 1468) and is known for his patronage of art, culture, and architecture in the 15th century.

Dharna Shah was a devout Jain businessman from the Porwal community. He worked in the court of the Rana Kumbha. On account of his hard work and commitment, Dharna Shah had grown to be a minister in Rana Kumbha’s court.

Dharna Shah had a dream in which he saw a vision of Chakreshwari Mata, the Yakshini or guardian Goddess of the first Tirthankara, Rishabhanatha. The Goddess showed him the beautiful form of a mythical celestial air-borne vehicle known as Nalinigulma Vimana, a flying palace of sorts, belonging to the 12th heaven, according to Jain cosmology.

In the mind of Dharna Shah, the Ranakpur Jain Temple with all its grandeur had already taken birth.

Dharna Shah sought the land to build the temple from King Rana Kumbha. Not only did he give a big piece of land to build the temple on, but he also asked Dharna Shah to build a town around it. The name Ranakpur is derived from the name of the king Rana Kumbha.

It now only remained for some gifted architect and a team of skilled workers to give that dream that he had to be given a concrete shape. Dharna Sheth in his quest for building a grand temple to Rishabhanatha invited numerous architects, artists, and sculptors and explained to them what he visualized. They in turn interpreted his vision and submitted their plans and designs for the proposed temple. But, alas, none of these came even close to the grandeur that Dharna Shah envisaged.

It was then, that destiny, sent a sculptor named Depaka (Depa) from a nearby village called Mundara to Dharna Shah. Depaka, also known as Depa or Shilpi Depa, was passionate about his work. He presented his plan, and Dharna Shah was elated. He had found the man who would help him shape his dream into reality.

Soon, the land for the temple was identified and procured through the patronage of King Rana Kumbha and the construction of what would be one of the most beautiful Jain temples started in right earnest in the year 1439 AD, near the slopes of the Aravalli hills. More than 2,500 artisans worked on the temple under the direction of Depaka Shilpi to give shape to the vision of Dharna Shah.

It took five decades to complete the construction, and it was younger brother of Dharna Shah, Ratna Shah who carried on the work to complete, ultimately becoming one of the most splendid Jain temples in India.

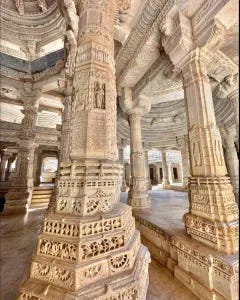

The temple complex houses a total of 1,444 marble pillars, and each pillar is 45 feet in height, is distinct in design. The pillars are individually carved and no two pillars are the same. Legend says that it is impossible to count the pillars. It is a melding of both symmetry and geometry to perfection. The architectural expertise of the builders is such that there is no sense of overcrowding, the pillars are aesthetically arranged so aligned that one can have an unobstructed view of the sanctum sanctorum from any position in the halls that surround it on all four sides.

The massive temple, a magnificent wonder in marble, stands entirely on the 1444 pillars that support it. There are no supporting walls inside the Chaumukha temple. The architectural marvel of the temple is such that it stays cool in hot summers and provides warmth during winter nights.

Interestingly there is no electricity inside the temple and the only available light is daylight and the architecture supports the place getting naturally illuminated. As a result the light through the day makes the place glow up in different colours though the hours of the day. As the sun rays shift through the day the pillars colour change from golden to blueish in the mandap (prayer hall).

The symmetry and design of the Ranakpur Jain Temple looks perfect, well almost! If you look carefully, you shall find one pillar that is slightly askew. You may wonder about this little imperfection in an otherwise perfect example of architectural design. However, the pillar in question has been deliberately built slightly askew, to ward of the effects of the “evil eye,” according to local and traditional belief.

The domes of the Ranakpur Temple are not only architecturally significant but also artistically and spiritually significant. They are a testament to the Jain tradition’s emphasis on intricate detail and devotion to art and religion. When you visit the temple, you’ll be able to marvel at the exquisite craftsmanship and the stunning beauty of these domes, which are an integral part of the temple’s overall magnificence.

The main dome is exquisitely designed with intricate marble carvings and sculptures. The carvings depict celestial beings, floral motifs, geometric patterns, and scenes from Jain mythology. The dome’s architecture incorporates concentric rings of ornate marble, creating a mesmerizing visual effect when viewed from below. The central part of the main dome is adorned with a lotus-like structure, adding to the overall aesthetic appeal.

On the ceiling of Meghanad Mandapa on the western side can be seen the beautifully carved Kalpavriksha, also known as the Kalpataru or the “Wish-Fulfilling Tree,” is a significant symbol in Jainism, Hinduism, and other Indian religions. It represents a divine tree that grants wishes and fulfills desires. In the context of Jainism, it symbolizes spiritual enlightenment, liberation, and the realization of ultimate truth.

Two huge bells, each weighing 108 kilograms made from panchadhatu, hang on either side of the sanctum sanctorum. One of the bells is referred to as male while the other is female. The difference is based on the sounds that the bells produce. The female bell produces a softer note while the male bell produces a louder note. These bells are rung together at the time of arati and their pealing resonates across the temple premises and the sound is believed to carry to a distance of a few kilometers.

Outside the sanctum sanctorum, on three sides can be seen the stone sculpture of identical elephants. Astride the elephant is the mahout and behind him is seated the figure of Marudevi, the mother of Rishabhanatha. It is believed that Marudevi went on an elephant to Shatrunjai hills to see her son, and died on the back of the elephant on which she was seated and attained moksha.

An intriguing carving of a man with one head and 5 bodies can be seen at the entrance hall of the temple, this is that of Kichaka who according to Jain Mythology was not killed by Bheema in the Mahabharata, but was punished and let off, he later became a Jain Monk, the figure of Kichaka is said to represent the 5 elements of nature

These are highly ornamental decorations carved from single sandstone slabs, there are three of these which adorn the halls of the temple, it is believed that there were originally 108 of them, and the majority of them were destroyed by the marauding forces of Aurangzeb.

King Rana Kumbha wished to make a victory tower called Kirti Stambh for his fame. but as divine power would have it, it remained incomplete and it is called adhuro-thamblo or ardha-stambh - the incomplete pillar.

There is a wonderful legend associated with this incomplete pillar. The story goes that Rana Kumbha who ruled over Mewar had provided the land for the construction of the temple. He had wanted a huge pillar to be built in his name.

On seeing the wonderful temple being built by Dharna Shah, King Rana Kumbha got insecure and thought that Dharna Shah would get famous through the temple but no one would remember him.

Thus thinking, he declared that he’d build one tower in the temple which would be dedicated to him. This tower being built with a feeling of self-pride and ego (instead of devotion towards the Lord) would be completed every night and then would be found demolished in the morning upto a certain height (The height of the main idol). Every day, the pillar would collapse after the workers had left for the night. As this went on repeatedly, Rana Kumbha realized that this was a providential lesson for him to overcome his ego. He ordered that the pillar be left incomplete, as a sign of the defeat of his ego. The pillar came to be known as ‘Ardha-stambh’

The temple houses 9 underground vaults, in which idols could be preserved in the event of crisis. It is believed that there are many idols still present in these underground vaults.

In the inner courtyard near the sanctum sanctorum, there is a Rayan tree (Manilkara Laxandra) which is believed to be 800 years old, beneath the shade of this tree are the footsteps or pagla of Bhagwan Adinatha or Rishabhadev. It is believed that this tree was planted by Sheth Dharna Shah, when he started the temple construction. Shree Aadinath Bhagwan has given his first sermon in Samavasaran under a Rayan tree and hence the tree is considered very sacred. Also, Rishabha dev attained Moksha or omniscience under Rayan tree.

Sahasrafana Parshvanath sculpture, carved from a single block of marble this depicts the 23rd Tirthankara Parshvanath in Kayotsarga pose flanked by the guardian deities Padmavati and Dharnendra, the hood of the 1008- headed mythical serpent Sahasrafana (a cobra with thousand hoods) forms a protective umbrella over Bhagavan Parshvanath, the intertwined tail of the serpent is so intricately carved that it is impossible to trace the end.

Samavasaran of Lord Mahavira, the 24th tirthankara is artistically made on a single marble — Jambu Dweep

Akbar (ruled 1556 to 1605) was keen to know the principles and doctrines of all contemporary religions and held a series of debates in the Ibadat khana of Fatehpur Sikri. Abul Fazl lists the names of a number of Jain saints of the Shwetamber sect who attended the discussions in the Ibadat khana. One of them was Jain Acharya Harvijai Suri.

An inscription is found on a pillar in Ranakpur temple (photo), where it is mentioned that influenced by Jain Acharya Harvijai Suri’s teachings the emperor promised to issue an edict to forbid killing of animals, hunting on the temple grounds.

When the Mughal Emperor Akbar visited this temple he was full of admiration and he had made an inscription on one of the columns, which says, that no one ever will be allowed to destroy this jewel of architecture

Revival of the temple. The original beauty and splendor lasted only for 200 years. The irony is that Aurangazeb, grandson of emperor Akbar who had given the edict to protect this temple, was the one who plundered and desecrated the temple. The magnificent masterpiece of a temple soon declined into oblivion.

It was overgrown by thick bushes and became the haunt of bats and reptiles, and other undesirable elements, pigeons roosted there and dirtied the portals of the sacred temple. Miscreants started using the area for their nefarious activities, and people stopped visiting the temple as the area became dangerous. The air which was once filled with the divine fragrance of incense was now pervaded with the stench of bird droppings and other filth. The temple became so desolate, devotees stopped visiting as the area was perceived as dangerous owing to the presence of wild animals and anti-social elements of society.

Credit of this temple’s revival and resurrection goes to Shri Kasturbhai Lalbhai, the chief of Sheth Anandji Kalyanji Trust. Over 200 workers and artisans dedicated themselves to the reconstruction of the Great Temple.

If you notice carefully the color variation in the sculpted stones clearly distinguishes the old and the new work done for restoration (photo above).